بَدِیۡعُ السَّمٰوٰتِ وَالۡاَرۡضِ ؕ وَاِذَا قَضٰۤی

اَمۡرًا فَاِنَّمَا یَقُوۡلُ لَہٗ کُنۡ فَیَکُوۡنُ

Originator of the heavens and the earth, when He determines the coming into being of a thing, He says concerning it: Be! and it is.

Quran 2:118

Introduction

During the Islamic Golden Age and beyond, the debate on the Eternity of the Universe was one of the greatest philosophical and theological discourses. Intuitively, the notion of the universe being eternal, specifically past-eternal, seems contradictory to the notion of God as a creator. However, renowned Muslim philosophers such as Al-Farabi, known as the ‘second master’ after Aristotle, and Ibn Sina, worked tirelessly to reconcile this Aristotelian and Neoplatonic concept with the Qur’an.

On the other hand, scholars of the kalām (theology) movement such as Al-Ghazali challenged them on both philosophical and theological grounds. The controversy and importance of the debate stems from the consequences the answers have for the essence and attributes of God and the interpretation and position of the Qur’an in the search for truth.

In this article, I will argue that the adaptation of Greek philosophical notions on the essence of God eroded the core of Islamic beliefs and practice. In agreement with Ghazali, I will argue that such an adaptation results not only in theological absurdity, but also in logical incoherence.

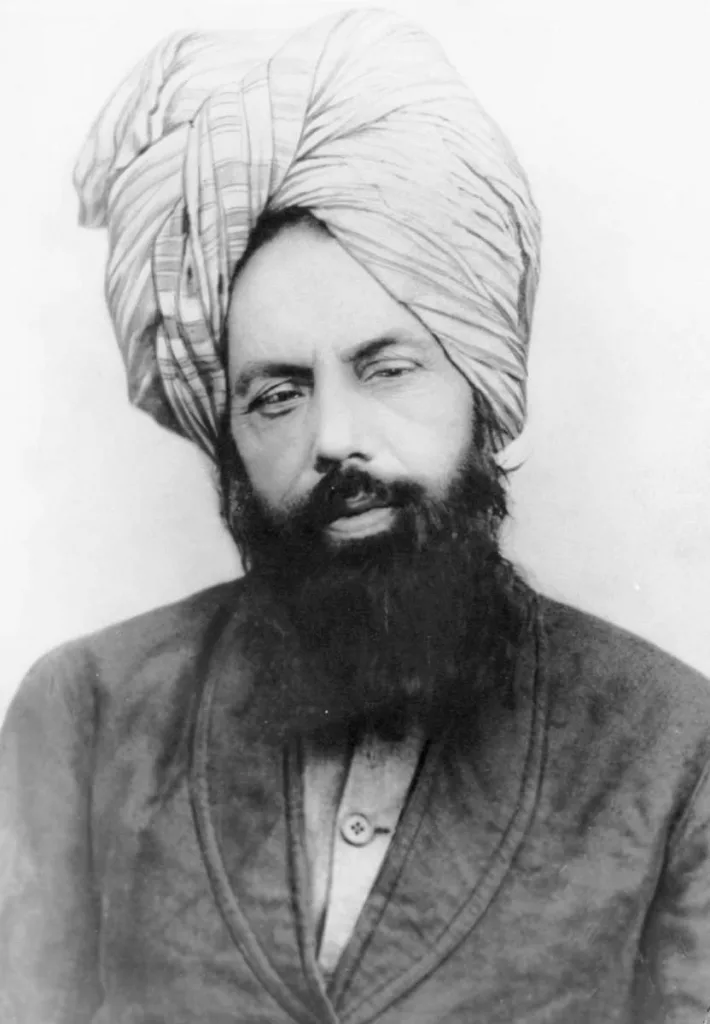

I will then present the views of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, the founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, on the relationship between reason and revelation, and explore the Ahmadiyya view that true intellectual pursuit flourishes when guided by divine revelation.

Greek Philosophy in the Islamic World

The tradition of philosophy in the history of the Islamic world expands beyond the Greek legacy. For the debate surrounding eternity, however, the ancient works of Aristotle and Plato, as well as those of the Neoplatonists — Plotinus and Proclus — were of great importance. Therefore, it is crucial to first examine the historical context of Greek philosophy in the Islamic world.

When the Muslims conquered Syria and Iraq in the seventh century, the Syriacs were already engaged in the translation of ancient works. During the early Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad the translation movement gained new support and recognition. Haroon al-Rashid and his son Al-Ma’mun founded the House of Wisdom, which would serve as an institute of translation for centuries to come. It was through this patronage that the translation of and elaboration on Greek and Syriac works of philosophy (falsafa), medicine and other sciences was institutionalized.1

Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, wrote Enneads. Another influential work on Neoplatonism was the Elements of Theology by Proclus. Both works were among the first to be translated into Arabic and were crucial to the development of falsafa in the Muslim world. The translators had great admiration for Aristotle and translated his Metaphysics and De Caelo. While translating Proclus’ Elements of Theology they attributed his work to Aristotle, naming it the theology of Aristotle. As the Greek works were assimilated into the Muslim milieu, the philosophers agreed on general assumptions which would trademark falsafa.

First, philosophy is systematic and relies on logic, the peak of which is rational theology. Second, all Greek philosophers agreed on certain doctrines concerning the cosmos, the soul and the first principle. Third, philosophical truths might align with the Qur’an, but they are not derived from it.2

These principles show that the Muslim philosophers took the philosophical conclusions on which the Ancients, especially Aristotle and Plato, were in consensus on as reliable knowledge. As demonstrative knowledge (burhān) is the most certain form of knowledge according to the philosophers, the conclusions derived from coherent syllogisms were placed on a pedestal for the Qur’an to be reconciled with.

“Certain knowledge about existence and cause is called in an absolute sense ‘demonstrative knowledge.‘” 3

The philosophers exalted reason as the most certain source of truth exclusively for the intellectuals to understand and claimed that the Qur’an speaks in metaphors for the common man to understand. Although they did not deem Scripture superfluous or contradictory to reason, they did claim that if the Qur’an is incompatible with their proposed syllogisms, which were inspired by Greek philosophy, then the Qur’an should be understood allegorically.

Thus, in their view, true understanding, including true knowledge of the Qur’an, could only come from reason and philosophy, and is thus to be understood through philosophy.

Neoplatonism

The issue which Neoplatonism, founded by Plotinus, deals with primarily, is the concept of how God, the soul and matter relate to one another. Prior to Plotinus, both Plato and Aristotle reached the conclusion that there must be an initial cause. For Plato this was the Craftsman (demiourgos) and for Aristotle this was an Intelligence (nous). Plotinus argued that the ultimate cause, which he called ‘The One,’ must be unchangeable and unmoved. As such, the act of creation, and the ever-changing nature of a created world, is incompatible with the unchangeable nature of an ultimate cause.

To resolve this issue, Plotinus posited a separate primary creative agent — the Intelligence — which emanates from the One in the same way that light emanates from the Sun. Plato’s Craftsman and Aristotle’s Intelligence are similar to Plotinus’ Intelligence; that is, he ascends the true divinity up one step, to ‘The One’, and posits the creative actor as a downstream ‘emanation’ which acts as the source of creation.

But the story doesn’t end there. The Intelligence (the Divine Vizier) has further emanations, through which the soul and particulars are created. The Neoplatonic theory therefore characterizes God i.e., the One, as a remote, unchangeable, and ultimate cause, whose direct involvement in temporal creation is deemed incompatible with His immovable nature.4, 5

This supposed conflict between God’s unchangeable perfect nature and the imperfection of Matter, i.e., creation, was first introduced by Aristotle. Aristotle proposed that God is the perfect unmoved mover, which does nothing but think of His own perfect nature, as Him thinking or doing anything else would subject him to change. Matter, he contended, is in a constant struggle to imitate God’s perfection. The Neoplatonic emanationist view adopted by Muslim philosophers is therefore an attempt to reconcile Aristotle’s unmoved mover with the religious notion of a Creative, Omniscient and deeply involved God, one who creates the world, creates life, sends revelations, and answers prayers.6

The Quran describes such actions as being intentional and purposeful. However, the theory of emanation which Ibn Sina and Al-Farabi defended and elaborated upon, contradicts the Creative and Omnipotent attributes of God in the Qur’an, as it describes the emanation of the Intelligence from God as being necessary and involuntary. As light proceeds from the Sun, the Neoplatonic thesis of “From the One, only one proceeds” continues in Ibn Sina’s works.7

God is thereby reduced to the direct cause of only one thing, the Intelligence, and only through this agent is indirectly responsible for all creation.8 The philosophers equated emanation with creation which shows that the philosophers attempted to adapt Aristotelian philosophy and Neoplatonic theories to Quranic notions. The philosophers thus interpreted Quranic verses about creation in accordance with the theory of emanation and aimed to reconcile the two.9

Ibn Sina’s Philosophy

Eternity of the Universe

The proposed eternity of the universe, mainly past-eternity, goes hand in hand with the theory of emanation as they essentially argue from the same premise. The idea is that God is eternal, and since God cannot create anything unlike Himself, nothing temporal can come from the Eternal. Aristotle’s ideas about eternity and the nature of time were influential on both Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina’s theories, though the latter parted from him in certain areas.10

Ibn Sina’s argument in favour of an eternal universe rests on the distinction between essential (ontological) priority and temporal priority. Ibn Sina argues that it is necessary for God to have essential priority to the universe, but not temporal priority. In fact, he argues that essentially ordered causes must exist at the same time as their effect.11 For example, the Sun is not temporally prior to its light, but has essential priority to its light. The light is completely dependent for its existence upon the Sun, but this does not necessitate temporal priority.

Ibn Sina goes on to argue that if the universe was temporally created, then it must have always been possible to exist. For it to have always been possible, there must have been a physical substrate that could manifest this possibility, thus, matter must have be eternally extant with God. 12

The next argument is founded in Ibn Sina’s understanding of the nature of time, which was inspired by Aristotle. The first premise is that time is dependent upon motion. He argues that if the universe was created at a particular moment in the past, there must have been a time before that moment. As time is dependent upon motion, there must have been motion. Then, there must be something undergoing motion, which is a form-matter composite. Thus, there must have been matter before the existence of the universe, which again results in logical absurdity, unless, as Ibn Sina claims, the universe is eternal.13

The Muslim philosophers further claimed, in agreement with Aristotle, that it is impossible that anything temporal is directly created by an eternal God. They theorised that for the universe to have been created temporally, there must have been a ‘determining factor’.14, 15

To illustrate this, imagine a person who has never written a book before. The idea for a book has never been formed, nor has a book ever been written. One day, the author sees the need for a certain book to be written and decides to author it. This inspires him to think of the content and he goes on to write and publish the book. In this example the author’s sudden need for a certain book to be written is the ‘determining factor’.

The philosophers further argued that to bring the world into existence from non-existence, the eternal God would also require a ‘determining factor’ to arise. The ‘determining factor’ emerging changes the eternally unchanging essence of God and would raise an infinite regress of determining factors. The philosophers, therefore, argued that for God to be eternal He must either be always creating something or never creating anything. Thus, they conclude that the universe is eternally existing parallel to God, though eternally dependent upon God.16, 17

God’s Omniscience

God’s image in the framework of the Muslim philosophers does not only reconceptualize the Creative attributes of God, but also His knowledge. Ibn Sina and Al-Farabi defended the position that God has complete knowledge through his knowledge of universals but does not know particulars. To understand the difference between universals and particulars, one can understand it as the difference between the universal concept of “tree” versus a particular tree, such as “the tree in front of my house”.

Ibn Sina illustrates his view on God’s knowledge through the example of an eclipse. An astronomer knows the eclipse through the process of witnessing it, which is a temporally changing knowledge. However, Ibn Sina argues that if God would have such knowledge of contingent matters, it would imply that His essence would become changeable. God, in Ibn Sina’s view, knows the universal concept of an “eclipse” from the eternal perspective of a creator. His knowledge in a universal sense encompasses all possible eclipses. Ibn Sina argues that this position protects God’s knowledge and His essence as unchangeable. However, Avicenna believed that God does not know each particular eclipse in the temporal, changing way that humans do, but rather knows them through His universal knowledge as their distant cause.18

Ibn Sina argued that God is pure intellect, thus pure knowledge, and his essence has no relation to time or matter, for His knowledge of particulars would make God’s nature changeable, which is impossible.19 As Imam Ghazali explained, the philosophers’ God does not know the actions of Zayd or Khalid distinct from one another; rather, He only knows the universal concept of ‘man’ and the universal concepts of ‘man’s actions’ and properties.20

Imam Ghazali’s Refutation

Eternity of the Universe

Imam Abu Hamid al-Ghazalirh rejected the Neoplatonic beliefs of the Muslim philosophers and sought to demonstrate its philosophical contradictions and theological consequences in The Incoherence of the Philosophers. In this work, Imam Ghazali elucidated the strongest proofs of the philosophers in favour of the eternity of the universe and refuted them.

Ghazali rejected the premise that the temporal world is impossible to come from the Eternal God, stating that the philosophers never demonstrated this. He argued that the philosophers have given no logically binding syllogism that excludes temporal creation from an Eternal Creator — there is no ‘middle premise’ between the existence of the Eternal Will, and the conclusion that temporal creation is impossible. It is simply a belief that is issued by fiat.

He pointed out that such a conclusion is clearly not intuitive, given the vast number of people who adhere to the belief that temporal creation is compatible with an eternal Creator. Thus there is no a priori reason to be suspicious of such a belief, and there is no obvious contradiction.

Through his extensive study, Imam Ghazali was able to show that the philosophers have only demonstrated an analogy to human intentions to support their thesis, which is a flawed comparison; whether or not humans need a determining factor before action is irrelevant, since the eternal Will is by essence not analogous to the human temporal will. 21

Ghazali then went on to reject the idea that human volition does not have an inherent capacity to distinguish between one thing and its like, thereby cutting down the analogy used to argue that an Eternal God would be incapable of creating a temporal universe.

What is notable in all this was Ghazali’s ability to use the very philosophical reasoning that the philosophers used against their doctrines:

Firstly, is your assertion that such a thing is inconceivable based on self-evident facts, or on theoretical investigations? In fact, it is not possible for you to make either claim. Your comparison of the Divine to human will is as false an analogy as that between the Divine and human knowledge. The Divine knowledge is different from ours in respect of things which we have established. Why, therefore, should it be improbable for a similar difference to exist in the case of will? 22

Ghazali further pointed out the conflation between eternal possibility and eternal existence in the framework of the philosophers. He argued that the eternal possibility for the world to exist does not necessitate its actual eternal existence, in the same way that the rational possibility of infinite spatial extension does not necessitate an actually infinite spatial body.23

Furthermore, Ghazali rejects the argument that it is necessary that the past must be eternal, and that therefore matter in motion to have existed eternally too. Ghazali states that God exists in a manner which transcends the framework of time. To explain this Ghazali compares time to space; he argues that spatial extension is a necessary concept accompanying the body, in the same way temporal extension is a necessary concept accompanying motion. As man exists in motion and matter, space and time are constructs in the human imagination. Thus, the tendency for the human reason to think in terms of ‘before’ the existence of the world, or ‘above’ the world are mere constructs, and not rational necessities.24

The next refutation which Ghazali presented focused on the supposed necessity for eternally-existing matter in order for the world to be eternally possible. While the Muslim philosophers argued that an eternally possible world would need pre-existing matter in order to be shaped into actuality, Ghazali rejects this by noting that ‘possibility’ is a mental estimation of conceptual coherence, independent of matter. He illustrates this by giving the example of the mind being able to conceptualize blackness or whiteness independent of any material body, thus logical possibility transcends the physical realm of matter.25 In doing so, Ghazali removed the final need for positing eternal matter in motion, allowing for the temporal creation by an Eternal Creator.

As part of his refutations, Ghazali was able to demonstrate a beginning of the universe, by proving that ‘past-eternity’ was an incoherent concept. For the universe to be eternal, it would have to have an infinite number of days in the past. He asked simply: is this infinite number even, or odd? If it is even, then we can add one to it and make it odd. If it is odd, then we can add one to it and make it even. He did this to demonstrate that a numerical infinity cannot be actually realised — potential infinity cannot be applied to the actuality of the universe. Potential infinity cannot be exceeded nor can it be completed, thus infinity would render reaching the present impossible. However, we have in fact reached the present, which means that the past cannot be infinite.

And if the past is not infinite, then the universe has a beginning.

Compatibility With Islam

The heart of Imam Ghazali’s critique was in highlighting the flaws in apparently sound reasoning, and in our wider reliance on philosophical thinking. In this case, such notions have in part been inherited from Greek predecessors, and the flaws in their reasoning. Such defects have consequences for our understanding of true divine cognisance, and our relationship with God, prophets, and revelation.

For instance, Al-Farabi narrates the nature of prophets and the process of revelation in the following way:

“This man is the true prince according to the ancients; he is the one of whom it ought to be said that he receives revelation. For man receives revelation only when he attains this rank, that is, when there is no longer an intermediary between him and the Active Intelligence. (…) This emanation that proceeds from the Active Intelligence to the passive through the mediation of acquired intellect is revelation.”26

A few aspects of this perspective on revelation are especially striking. First of all, in describing the prophets, i.e., the true prince, Al-Farabi evaluates them through the conceptual framework of the Ancients (the Greeks), exemplifying the position held by the them in the truth-seeking efforts of Muslim Neoplatonic philosophers.

Furthermore, the intermediate position of the Active Intelligence is contrary to the Islamic belief of God’s direct revelation to His people. Although it may be proposed that the angels are the embodiment of this Intelligence, the notion that God is only an indirect cause behind revelation as He is an indirect cause of all other creation, according to the theory of emanation, degrades God to a merely necessary cause.

If one accepts that God is only the necessary, though indirect cause of revelation, and indeed the indirect cause of all other creation, and that knows His creation only in a universal sense, then why do we worship God? In accepting the thesis of the philosophers, one could argue that the emanating agents are more influential over our lives, and therefore more worthy of our prayer. Or, if all emanating agents are necessarily causing everything which is created, and if God necessarily emanates the Agents, then why should one pray at all?

There is naught by necessity, with God having no intention or agency. This degrades God to the deistic and passive position as the unmoved mover and has destructive consequences to the meaning of revelation. More importantly, it has destructive consequences for the purpose of life proposed in the Qur’an, that is, to worship God and establish a true, loving relationship with Him.

Ghazali critiqued the philosophers on several consequences their theory has for the attributes of God and His importance in the lives of believers. He says:

“Do not confuse matters by [stating] that God is the maker of the world and that the world is His doing. For this is an expression which you have uttered, but [you have] denied its reality. The purpose of this discussion is only to clear this deceptive beclouding.”27

Ghazali was pointing out that the religious convictions of the philosophers were unjustified — verbally assented to, but not substantiated by their actual philosophy. To call God ‘Maker’ when he was eternally co-existent with Creation, was insincere.

God’s Omniscience

For Ghazali, the same problem threatened God’s omniscience, in their explanation of God’s knowledge of particulars. Ibn Sina’s argument states that God is not entirely deprived of particular knowledge, rather His knowledge is from the perspective of a cause; particular knowledge through a universal lens. This view faces the immediate challenge of whether it really answers the ‘problem’ of God’s immutability which the philosophers dealt with in the first place. For if God has universal knowledge of particulars, as their cause, this kind of knowledge does not rule out multiplicity or temporality in God’s knowledge, as pointed out by the 12th-Century thinker Al-Shahrastani.28

In addition, in Al-Razi’s critique of Ibn Sina notes that if God knows his creation as its cause, then surely he should know the grounds on which its effects differentiate themselves. Therefore, God’s knowledge becomes that of particulars, not of universals. Moreover, thinkers within the Avicennan tradition, who adhere to a purely universal view of God’s knowledge, critique Ibn Sina’s position by arguing that God’s universal knowledge is unable to give knowledge of a particular. This is because, irrespective of the combination or the specificity of universals, in theory this combined set of universals could very well be presented in different particulars. Thus, not only does Ibn Sina’s view of God’s knowledge create a vast void between God and His creation, it also reveals several philosophical incoherencies and contradictions.28

It was for these reasons that Ghazali charged the philosopher’s God as not knowing Zayd’s belief or unbelief. He only knows man’s belief and unbelief as a universal concept. Thus, Ghazali states, following the notions of the philosophers, God would not have known the actions of the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa and all other prophets.20 To place a personal relationship with God and His involvement in individual lives in the realm of allegory, and outside of God’s actual knowledge, undermines the fundamental reason for religion, as revealed by God Himself.

In the same vein, the philosophers imply that God is not able to receive individual prayer, or to know the repentance of His believers, nor is He able to act upon those prayers. Thus again, the adaptation of Greek philosophy into Islamic thought made God into a distant and detached entity with little influence on our everyday individual lives.

This reconceptualisation is completely contrary to Quranic verses about God and the practices of the Prophet. If the Qur’an speaks in metaphors about God’s involvement and knowledge of His creation, and truly God’s knowledge is only universal, then why do the prophets in their practice prioritise worship to achieve nearness to God? Why does the Quran state:

“And with Him are the keys of the unseen; none knows them but He. And He knows whatsoever is in the land and in the sea. And there falls not a leaf but He knows it; nor is there a grain in the deep darkness of the earth, nor anything green or dry, but is recorded in a clear Book.”

Holy Quran, 6:60

Such philosophical ideas not only fail to defend the essence of divine attributes but also threaten to reduce worship, and religion more fundamentally, to a mere intellectual exercise devoid of a personal connection to God.

The Ahmadiyya View

Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas (1835-1908), the Promised Messiah and Mahdi and the founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, addressed the questions about knowledge, certainty, and the relationship between human reason and divine revelation with profound insight.

Ahmadas lived during an age when religious belief and practice was increasingly challenged by scientific materialism and pure rational philosophy. Faith in One living God was rapidly declining. Thus, Ahmadas pointed out the consequences of relying solely on human reason for understanding metaphysical reality in the philosophical errors of both ancient and modern thinkers.

“The harm that has been done to the world by pure reason is not a hidden matter. What made Plato and his followers deny that God is the Creator? What made Galen doubt the immortality of souls and the reality of Judgement? What made philosophers deny that God has knowledge of all particulars? What made great philosophers worship idols? What led to the sacrifice of roosters and other animals before idols? Was it not reason unaccompanied by revelation?”29

Hazrat Ahmadas argued that reason suffers from a fundamental limitation: it can establish the logical necessity of something (that it “should be”) but cannot by itself confirm actual existence (that it “is”). This distinction between possibility and actuality represents the gap only revelation can bridge in the domain of metaphysical truth. He states:

“It is true that reason is also a lamp which God has furnished to man, the light of which draws man towards truth and saves him from a variety of doubts and suspicions and sets aside different types of baseless ideas and improper conjectures. It is very useful, very necessary and is a great bounty.

Yet, despite all this it suffers from the shortcoming that it alone cannot lead to full certainty in the matter of the understanding of the reality of things. (…) So, God Who is most Compassionate and Generous and desires to lead man to the stage of utmost certainty has fulfilled this need and has appointed several companions for reason and has thereby opened the way of perfect certainty to it, so that the soul of man, whose total good fortune and salvation depends upon perfect certainty, should not be deprived of its desired good fortune and so that it should quickly cross the delicate and dangerous bridge of ‘should be’ which reason has constructed over the river of doubts and suspicions, and should enter the grand palace of ‘is’ which is the house of peace and satisfaction.”30

Hazrat Ahmadas articulated how one crosses this bridge to reach certainty in different domains of knowledge. Depending on the type of knowledge being sought, a different companion is appointed to reach certainty. He distinguishes knowledge of observable phenomena, knowledge of historical and temporal matters and knowledge of metaphysical realities from one another.

For observable phenomena, or empirical knowledge, first-hand experience and observation are reason’s companion. This allows reason to move from assumption or hypothesis to verified knowledge about the physical world. When reason investigates historical or temporal matters, its companions are historical artefacts, documented records and testimonies. These sources provide the factual foundation to reach certainty about past events. For metaphysical realities, however, reason requires revelation as its necessary companion. When reason explores the unseen realities of divine existence, the nature of the soul and the afterlife unaccompanied by revelation, it remains trapped in the realm of speculation.31

“The Word of God directs us: Have faith and you will be delivered. It does not tell us: Demand philosophical reasons and conclusive proofs in support of the doctrines that the Holy Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) has presented to you, and do not accept them until they are established like mathematical formulae. (…) It should be remembered that God Almighty, by demanding faith in the unseen, does not wish to deprive the believers of certainty of understanding the Divine. Indeed, faith is a ladder for arriving at this certainty of understanding, without which it is in vain to seek true understanding. Those who climb this ladder surely experience for themselves the pure and undefiled spiritual verities.”32

Muslim philosophers aimed to build a metaphysical construct which would align with the contemporary philosophical concepts, in part inherited from the Ancients, as well as the Qur’an, to achieve the highest level of certainty of belief. However, Hazrat Ahmadas writes that true certainty can only be achieved through the manifestation of God’s signs and his revelation upon man.33

What is true certainty and how do we reach this stage? He writes:

“As God has invested man with the faculty of reason for the understanding, to some degree, of elementary matters, in the same way God has vested in him a hidden faculty of receiving revelation. When human reason arrives at the limit of its reach, then at that stage God Almighty, for the purpose of leading His true and faithful servants to the perfection of understanding and certainty, guides them through revelation and visions. Thus, the stages which reason could not reach are traversed by means of revelation and visions, and seekers after truth thereby arrive at full certainty. This is the way of Allah, to guide to which Prophets have appeared in the world. Without treading this path, no one has ever arrived at true and perfect understanding.

But a poor dry philosopher is in such a hurry that he desires everything to be disclosed at the stage of reason. He does not know that reason cannot carry a burden beyond its strength, nor can it step further than its capacity. He does not reflect that, to carry a person to his desired excellence, God Almighty has bestowed upon him not only the faculty of reason but also the faculty of experiencing visions and revelations. It is the height of misfortune to make use of only the elementary means out of those that God has, out of His Perfect Wisdom, bestowed upon man for the purpose of recognizing God, and to remain ignorant of the rest. It is extremely unwise to let those faculties atrophy through lack of use and to derive no benefit from them.

A person who does not use the faculty of receiving revelation and denies its existence cannot be a true philosopher, whereas the existence of this faculty has been established by the testimony of thousands of the righteous and all men of true understanding have arrived at perfect understanding through this means.”34

The realization that achieving true certainty is not possible merely by following the path of demonstrative reasoning, or the path of kalām, or any other path that does not seek knowledge through direct guidance from God, was one Ghazali reached in his own search for the true path of knowledge.

In his autobiography, al-Munqidh min al-Dalāl (Deliverance from Error), Imam Ghazali recounts his intellectual and spiritual journey and describes his internal crisis in his search for certainty. After having been a teacher of Islamic theology for a large part of his career and having studied the philosophers and others, he concluded that the way of the Sufis was the best way to attain true knowledge. He writes:

“Indeed, were one to combine the insight of the intellectuals, the wisdom of the wise, and the lore of scholars versed in the mysteries of revelation in order to change a single item of Sufi conduct and ethic and to replace it with something better, no way to do so would be found! For all their motions and quiescences, exterior and interior, are learned from the light of the niche of prophecy. And beyond the light of prophecy there is no light on earth from which illumination can be obtained.”35

Hazrat Ahmadas illustrated the difference between metaphysical certainty through reason or through revelation with the analogy of a traveller. He explains that when a traveller, who is known for his truthfulness, speaks about his journey to faraway lands, those around him listen with deep affection. So much so that often the listeners are moved by the stories, as though they visited the lands themselves. Whereas when someone who has never left the four walls of his home speaks of those lands through his imagination and estimation, he becomes a laughing stock.36

Ahmadas explains in further depth that reason is not harmed by revelation, nor is revelation the enemy of reason and writes:

“When you will reflect truly it will become clear to you that God has not harmed reason by appointing revelation as its companion. On the contrary, finding reason perplexed, He has furnished it with a sure instrument for recognizing the truth through the use of which reason is saved from straying into hundreds of erratic ways and is not led astray.”37

This profound explanation of Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas shows that rationality is one of man’s faculties gifted to him by God in his pursuit of knowledge, thus ultimately in his pursuit of God. However, revelation is its greatest benefactor and supporter and will lead to true satisfaction and rational coherence in our metaphysical reflections.

One final aspect to note is the teaching of Hazrat Ahmadas that all recipients of revelation do not have the same rank, nor the same protection from errors in their reasoning. Thus, Hazrat Ahmadas differed from Imam Ghazali in some areas, such as the continuation of Prophethood, and had a more developed position on the nature of the afterlife and God’s relationship with the universe.

From the Ahmadiyya perspective, such disagreements with past saintly reformers is expected, since the position of the Imam Mahdi, which Hazrat Ahmadas is deemed to occupy, was special — he was to be the Hakam and ‘Adl — the one whom God would raise to determine the right course between differing Muslim views, at a time when the body of Islam would be overrun with internecine conflicts.

Conclusion

The philosophical discourse surrounding the eternity of the universe and the nature of God during the Islamic Golden Age reveals a critical flaw in the philosophers’ valuation of reason, philosophical tradition, and the Islamic God. The Muslim philosophers of the falsafa movement, notably Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina, placed disproportionate value on Greek philosophical traditions, implying the need for the Qur’an to be reconciled with Greek philosophy. This led them to reinterpret the core of Gods nature in ways that aligned with Neoplatonic and Aristotelian thought, resulting in a view of God as a distant and impersonal entity.

Although Islam values knowledge of other cultures greatly, one should always reflect upon whether this knowledge aligns with the Word of Allah and the practice of prophets. As any knowledge contradictory to these sources of truth will not only be theologically unintelligible, but also intellectually incoherent. Ghazali’s critiques, thus, highlight not only theological, but mainly philosophical inconsistencies, arguing that the philosophers’ syllogisms fail to provide a coherent framework to defend their position on the Cosmos and God.

Ultimately, this shows that reason alone or the knowledge of any predecessor or contemporary deprived of the fountain of knowledge, which is the Qur’an, is not sufficient to reach absolute and true knowledge, nor is it exhaustive to achieve nearness to God.

REFERENCES

[1] D’ancona, Cristina. “Greek into Arabic.” Chapter. In The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy, edited by Peter Adamson and Richard C. Taylor, 2004, p.18-21. [2] D’ancona, “Greek into Arabic”, 2004, p.21 [3] Al-Farabi, The Book of Demonstration in Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources, McGinnis and Reisman (Hackett Publishing, 2007), p.68 [4] Sedgwick, Mark, Western Sufism: From the Abbasids to the New Age, 2016, 19-20. [5] O’Meara, Dominic J., ‘The Derivation of All Things from the One (I)’, Plotinus: An Introduction to the Enneads, 1995, 62. [6] Ahmad, The Epistemology of Revelation and Reason, 1998, 44. [7] Ibn Sina, The Metaphysics of Healing: Al-Ilahiyat Min Al Shifa’, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2005), 330 [8] Amin, Wahid M. ““From the One, Only One Proceeds”: The Post-Classical Reception of a Key Principle of Avicenna’s Metaphysics”, p.123-4. [9] William Montgomery Watt, Muslim Intellectual: A Study of Al-Ghazali, 1963, p.60. [10] Adamson, Peter S. Philosophy in the Islamic World : A Very Short Introduction, p.61-67. [11] McGinnis, Avicenna, p.193 [12] McGinnis, Avicenna, p.196-7 [13] McGinnis, Avicenna, p.197-9 [14] The Incoherence of the Philosophers, “The First Discussion,” On Refuting Their Claim of the World’s Eternity, Al Ghazali in Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources, McGinnis and Reisman (Hackett Publishing, 2007), 242-5. [15] Ibn Sina, The Metaphysics of Healing: Al-Ilahiyat Min Al Shifa’, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2005), 302. [16] The Incoherence of the Philosophers, “The First Discussion,” On Refuting Their Claim of the World’s Eternity, Al Ghazali in Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources, McGinnis and Reisman (Hackett Publishing, 2007), 242-5. [17] Ibn Sina, The Metaphysics of Healing: Al-Ilahiyat Min Al Shifa’, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2005), 302. [18] Belo, Averroes on God’s knowledge of particulars, p.181 [19] Belo, Averroes on God’s knowledge of particulars, p.178-80 [20] Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 136-7.[21] Al Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, “The First Discussion,” On Refuting Their Claim of the World’s Eternity, Al Ghazali in Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources, McGinnis and Reisman (Hackett Publishing, 2007), 242-5.

[22]. Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Sabih Ahmad Kamali (Pakistan Philosophical Congress Publication No. 3, 1963), p26 [23] Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 39-40. [24] Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 32-5. [25] Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 40-2. [26] Al-Farabi, The Political Regime in The Epistemology of Revelation and Reason, Ahmad, 1998, 49-50 [27]. Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Michael E. Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 59-60. [28]. Peter Adamson and Fedor Benevich. “Chapter 11 God’s Knowledge of Particulars”, p.494-559. In The Heirs of Avicenna: Philosophy in the Islamic East, 12–13th Centuries, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2023) doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004503991_013] [29] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol. 2, p.104 [30] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol. 2, p.96-8 [31] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol. 2, p.96-8 [32] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol.3, p. 8-9 [33] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol.3, p.43 [34] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol. 2, p.37-8 [35] Al-Ghazali, Deliverance From Error: Al-Munqidh Min al-Dalāl, 21. [36] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol. 2, p.98-101 [37] Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Essence of Islam, Vol.2, p.95.BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adamson, Peter S. Philosophy in the Islamic World : A Very Short Introduction. First edition. Vol. 445. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015, 61-67.

Ahmad, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam, Essence of Islam – Volume II. Islam International Publications Ltd, 2004

Ahmad, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam, Essence of Islam – Volume III. Islam International Publications Ltd, 2004

Ahmad, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam. Malfuzat – Volume I. Islam International Publications Ltd, 2018. Ahmad, The Epistemology of Revelation and Reason, University of Edinburgh, 1998.

Al-Farabi, The Book of Demonstration in Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources, McGinnis and Reisman. Hackett Publishing, 2007.

Al-Farabi, The Political Regime cited in The Epistemology of Revelation and Reason, Ahmad, 1998

Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Michael E. Marmura, Brigham Young University Press, 2000.

Al-Ghazali, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, trans. Sabih Ahmad Kamali (Pakistan Philosophical Congress Publication No. 3, 1963)

Al Ghazali, The Incoherence of Philosophers in Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources. Hackett Publishing, 2007.

Amin, Wahid M. “From the One, Only One Proceeds”: The Post-Classical Reception of a Key Principle of Avicenna’s Metaphysics, Oriens 48, 1-2 (2020): 123-124, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/18778372- 04801005

D’ancona, Cristina. “Greek into Arabic.” Chapter. in The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy, edited by Peter Adamson and Richard C. Taylor. Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Ibn Sina, The Metaphysics of Healing: al-Ilahiyat Min Al Shifa’, trans. Michael Marmura (Brigham Young University Press, 2005).

McGinnis, Jon, Avicenna, (New York, 2010; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Sept. 2010) http://academic.oup.com/book/3244

O’Meara, Dominic J., ‘The Derivation of All Things from the One (I)’, Plotinus: An Introduction to the Enneads (Oxford, 1995; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Nov. 2003).

Sedgwick, Mark J. Western Sufism: From the Abbasids to the New Age, Oxford University Press, 2016. https://academic.oup.com/book/12370.

Watt, William Montgomery. Muslim Intellectual: A Study of Al-Ghazali, Edinburgh University Press, 1963.