Introduction

In 1930, Max Weber published his influential analysis of modern economic history, entitled The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. In this magnum opus, Weber argued that there is a close causal influence between the Protestant Reformation and modern western capitalism. In his view, the Reformation spurred on Western European nations to see money-making as a moral act. It thereby transformed the mundane into the spiritual, and has turned the wheel of economic progress to reach the modern day.

According to Weber, this moral and ethical spirit of capitalism is what distinguishes modern western capitalism with previous forms. These added ingredients gave the capitalism with which we are so familiar a distinctive spirit, with features that were not found elsewhere.

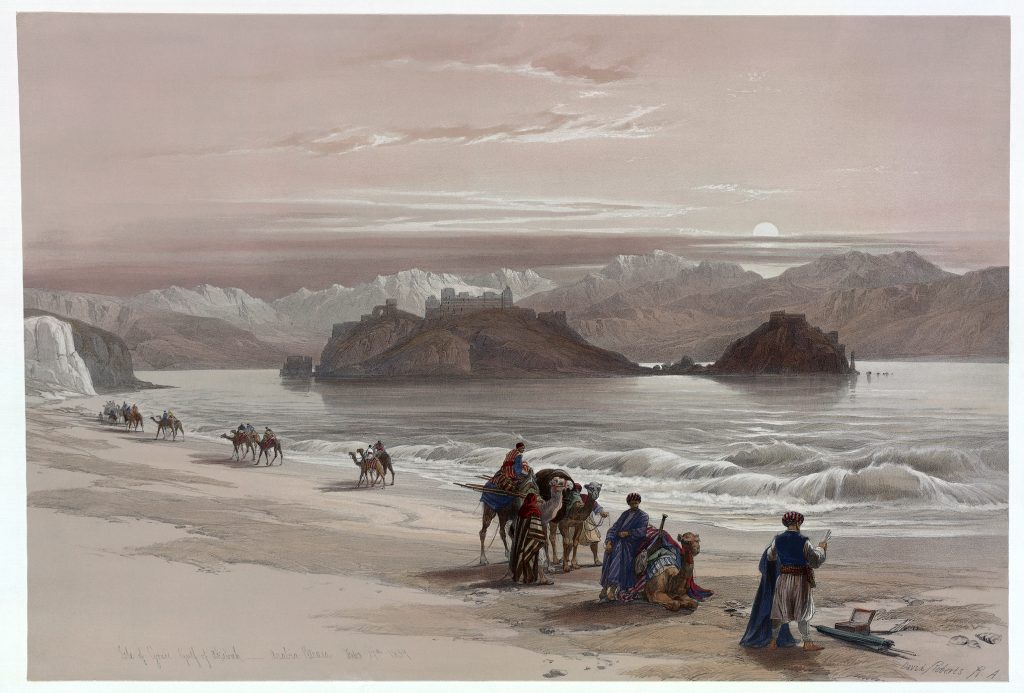

However, Weber’s sense of history is not far-reaching enough to draw this conclusion firmly. Capitalism has indeed existed in many forms, and a careful examination of Pre-Islamic Arabia unveils many similarities of that era with modern capitalism. The case of the city of Mecca is uniquely fascinating, not only because it was the city where the Prophet of Islam grew up, but also because Islam’s teachings were themselves an answer to the unfair practices of Mecca’s tribal capitalism.

The Rise of Mecca

At the outset, the overall situation of Mecca was very different from the southern states in Arabia. Mecca had neither an agricultural surplus nor a specialised productive industry of which it could boast. Nevertheless, Mecca was a place of refuge for commercial caravans travelling through the Hedjaz, the western part of the Arabian Peninsula, and allowed an initial form of accumulation of merchant capital in the region.

Until the beginning of the fifth century CE, Mecca was under the leadership of the Khuza’a, a tribe from Yemen. This was removed from power when Qusayy ibn Kilab reunited the various clans to form the Quraish tribe, and which quickly became the largest trading tribe of the city. Traditions tell us that it was Qusayy ibn Kilab who introduced many institutional practices that were new and revolutionary, putting Mecca on the path to rapid commercial growth. These institutions were: the rifada, (the provision of food to pilgrims); the siqaya (the provision of water to pilgrims); and the establishment of Dar al-Nadwa, a type of state house where clan leaders met to deliberate upon pressing issues (Ibrahim, 1990; M. B. Ahmad, 2011). In addition to the sadaqa (voluntary charitable alms), the rifada and siqaya practices formed a system of wealth distribution that aimed to deal with the economic stratification emerging in Meccan society as a result of increased trade. It is worth noting that the benefits of this system not only affected pilgrims, but also the poorest sections of the population of Mecca. These institutions played a dual role of both caring for pilgrims and merchants, and making the city a more attractive destination to visit.

Despite this, the institutional innovations of Qusayy did not eliminate all the obstacles faced by merchants in Mecca, especially as its efforts were directed towards the internal organization of the city (Ibrahim, 1990). In fact the limited accumulation of wealth often had disastrous consequences for some merchants in Mecca. This is illustrated by the events that preceded the introduction of the ilaf, a trade agreement, by Hashim ibn ‘Abd Manaf, Qusayy’s grandson (Hamidullah, 1957). Because of the restricted sphere of their commercial activities and the nature of their trade, merchants of Mecca were not immune from a financial catastrophe. These colossal losses occurred quite often, and in search of a solution to this problem merchants were forced to practice i’tifad (ritual suicide) (Kister, 1965). As a result, the merchant who lost his property was forced to separate from his family and the rest of the clan, letting them die from starvation. Hashim argued for a change in the nature of their businesses and proposed that if several merchants collect capital, their business positions would be more secure (mudaraba). This is significant because it both allowed merchants to procure some capital, and allowed the poor to regain their economic standing by providing new opportunities for social mobility. Subsequently, Meccans began to realize large-scale and collective commercial projects, while the individual investor was reassured and the risks minimized.

As Mecca’s growth and population skyrocketed, social stratification began to take concrete form. In fact the fiction of kinship served to mask the division of society into social classes (Wolf, 1951). At the top of the social ladder was the sayyid, the leader of the clan who was at the same time a merchant. His strength and influence depended mainly on his clan and the covenants he could muster. Then there was the ally (halif) of the sayyid who also enjoyed a respectable position. Then there were the members of the clan whose position depended on that of their clan as a whole. The clan, as a social unit, provided the initial infrastructure for the development of the power and wealth of the clan leader. At the bottom of the social ladder were mawalis and slaves. The mawla was weaker in social status than the sayyid, his ally and the clan. A set of devices were put in place so that the mawla redistributed all of the profit gained to his master, and thereby concentrated more and more capital in the hands of the sayyid.

If the mawla satisfied the terms of the agreement, then it was possible for him to become a halif. This is perhaps the real difference between the latter and the slaves (the qinn), and his descendants (the muwalladun). Like the mawla, slaves could be of Arab or non-Arab origin, but they had the peculiarity of being deprived of their freedom, having either been captured in times of war or being unable to pay their debts. The status of the qinn and of the mawla are indicative of the transformation of the social structure, to such an extent that some members of Meccan society were considered as products or tools for the benefit and service of the merchant leaders. It is then that the merchants, already pocketing a large part of the growth being generated, engaged in another practice to further increase their capital: interest (riba) (Lammens, 1910). It is difficult to determine when riba started to play an important role in Mecca. It is assumed that it certainly began after the introduction of ilaf practice, since trade increased in volume after it. Riba has thus played a dual role: it concentrated an enormous amount of wealth in the hands of a few, and while increasing inequality and further reducing the social status of the impoverished.

As well as the institution of new economic devices, it is hard to overstate the importance of tribal rivalries in the evolving Meccan political landscape. After Qusayy’s death, the Quraish eventually split into different factions. By the mid-6th century C.E., the clan of Banu Umayya were dominating both politically and economically. Their chief rivals were the Banu Makhzum. These tribes were led by Abu Jahl and Abu Sufyan respectively, who were competing for leadership in Mecca when Muhammadsa preached the new religion. It was this competition that facilitated Muhammad’ssa relative safety in Mecca for thirteen years before going to Medina in 622.

The Call of the Prophet Muhammad

In the year 610 of the conventional era, central Arabia was on the brink of a change that would not only shake its history, but also that of other nations for centuries to come. It is on this date that Mecca heard for the first time Muhammadsa proclaiming a new religion of which he was the Messenger. By the time Muhammadsa came on the scene, there was a clear tendency towards individualism in Mecca. Their economic culture concentrated wealth in the hands of a few to the exclusion of the poorest. These growing tensions within the system posed a threat to Mecca’s trading network, and the Qurayshites must have realised the inherent dangers of such an explosive situation. But no one made any warning as to the inevitable social and spiritual upheaval that this would bring to Mecca; nobody except Muhammadsa.

Initially, he preached to members of the Quraish tribe to put some order into their own house. The pursuit of excessive wealth, the privation of the weak, and the neglect of the poor in Mecca were all observations he considered as evils. It was therefore cooperation and the idea of justice between the rich and the poor that was the cardinal principle of Muhammad’ssa social teachings. However, it required the rich Qurayshites to make a certain sacrifice.

Although his early followers included affluent merchants such as ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affanra, few Meccans paid attention to his warnings. For thirteen long years, he continued to preach to his fellow citizens despite the great difficulties he faced. These difficulties became especially acute during the economic and social boycott of the Hashimite clan (Muhammad’ssa clan) which was stipulating to “cease trading with them, to not speak with them, to not marry their women nor give them our daughters” (Tabari, 2001).

From an academic perspective, to say that the Holy Book of the Quran is full of chapters evoking divine displeasure upon Meccan society is really an understatement. Meccans were invited to more moderation and flexibility, especially towards the poor, orphans, widows and all who were weak and in need of help. If wealth was described as an “ornament of the life of this world” (18: 47), he who deprived a large section of the population would have no status in the final analysis, as all individuals would be accountable before God (Torrey, 1892). Moreover, such deprivation was not economically sound because the widening gap between the rich and the poor had not only created social tension, but was forcing merchants to give up more of their wealth. As a result, they were asked to make their wealth more mobile by distributing it instead of accumulating it excessively. As one verse reads, “Mutual rivalry in seeking increase in worldly possessions diverts you from God; Till you reach the graves” (102: 2 & 3).

Indeed, was not the apocalypse that Meccans feared the most one in which “there shall be no buying, and selling, nor friendship, nor intercession” (2: 255)? The use of such analogies is very appropriate in the preaching of a message to a people whose love of trade bordered on obsession.

The Zakat

During the Meccan period, the Muslim community (umma) didn’t have anything that could be related to public finances. However, the economic foundations of the umma took many forms. A prevailing theme was cooperation among members to provide avenues for further economic development. A way of redistributing wealth was first offered to new emigrants to Medina, called, the mu’akha. This was a kind of fraternization that was translated materially by the transfer of capital from the Ansar (Muhammad’ssa Medinan supporters) to the Muhajirun (the emigrants or the first converts to Islam who emigrated with him from Mecca to Medina).

But in 630 C.E., the chapter about alms was revealed, and the teaching would become an important pillar of the Islamic faith. It took the name of “Zakat”, and its entire philosophy, meaning, and usefulness is contained in the word itself (S. M. Ahmad, 1975). The connotations of the Arabic word are of abundance and purification. The reasons are clear. Islam taught that the wealth and riches from which this tax was taken became blessed. Moreover, it taught that the original money would not suffer a loss, but would in fact become plentiful and immune from loss and depreciation. In fact, Zakat is the means of increasing, cleansing and purifying; of growth and of blessings, of ensuring protection from all sorts of calamities, and of submission to God.

Zakat isn’t a tax which is levied on one’s income. Rather, it is a capital tax spent wholly for the benefit of the categories mentioned in the Holy Book, outlined below. Islam has imposed Zakat on wealth and properties which have the attribute of increasing and multiplying and which could be preserved safely, for which reason it was assessed every year during which one has had ample opportunity to spend. It is on this principle that gold, silver, cash in any shape or form, goats, sheep, or cattle which feed themselves by grazing and all the produce from the land were assessable for Zakat.

As far as the beneficiaries are concerned, the Holy Book advises that “alms are only for the poor and the needy, and for those employed in connection therewith, and for those whose hearts are to be reconciled, and for the freeing of slaves, and for those in debt, and for the cause of Allah, and for the wayfarer.” (9: 60)

The first two categories of ‘the poor and the needy’ are self-explanatory, though the later differs from the former in that the sakeen (needy) are those who are either unable to advocate for themselves, or who refuse to do so out of their sense of self-dignity.

Under the category of those ‘whose hearts need reconciliation’ were the Muslims who, through a feeling of fear towards non-Muslims, could not declare themselves as such openly even though they were convinced in the wisdom and truthfulness of the message of Islam.

The money of Zakat was also used to free a person from the yoke of slavery. The slave in question did not have to be a prisoner of war, as the Arabic term “firiqab” also refers to people in a state of immense distress akin to that of slavery, such as a man who had been imprisoned for a long time due to the inability of honouring his debts.

Finally, under the heading “for Allah’s sake”, was added to cover expenses needed for the organization of an event, in which lay the protection or the progress of the nation.

It is impossible to question the importance of Zakat. On the whole it is not once, but twenty-seven times that it is grouped in the same verse recommending to observe the daily prayers (2: 44 ; 2: 84 ; 2: 111 ; 2: 178 ; 2: 278 ; 4: 78 ; 4: 163 ; 5: 13 ; 5: 56 ; 9: 11 ; 9: 18 ; 9: 71 ; 19: 32 ; 19: 56 ; 21: 74 ; 22: 42 ; 22: 79 ; 23: 3 & 5 ; 24: 38 ; 24: 57 ; 2: 4 ; 31: 5 ; 33: 34 ; 58: 14 ; 73: 21 ; 98: 6). This powerful instrument was unheard of before Islam, and it permits a redistribution of wealth on a large and unprecedented scale.

The Prohibition of Interest

In the first years in Medina, the prohibition of interest had immediate applicability towards the Jews (4: 161 & 162). Since Muhammadsa was in alliance with them, he had to call upon their contributions, either to support the emigrants from Mecca, or for military expenses and preparations (Watt, 1956). This was especially needed when an attack of Meccans was imminent. The call for contributions was made to Jews as well as to Muslims, but the former refused and declared themselves ready to make a loan with interest (Bukhari, #2068). As neighbouring citizens of the same nation, the Muslims expected the Jews to contribute to the national cause, or at least make interest-free loans. In this way, the question of interest became another sticking point in religious teaching between the teachings he expounded and the economic culture of the contemporary Jews.

However, a careful examination of the overall situation of Arabia shows that even before the prophethood of Muhammadsa, charging interest was a widespread practice, (in Mecca at least) and produced considerable difficulties for poorer classes. As a result, many transactions were discouraged mainly to prevent the practice of interest entering from the back door. Such was the case for muhaqala (the renting of land for gold) and mukhadara (the selling of green wheat before it was harvested for already harvested wheat). There were also the practices of m‘awama (selling the crop years in advance), kira’ (the buying of a crop before it was ripe or harvested in exchange for another crop), and the muzabana (the sale of grapes in exchange for raisins / wheat in exchange for prepared food).

The purpose of Islam cannot be reflected in purely economic terms, its objective being to improve the moral and spiritual state of Man. The types of duties assigned to Muslims were on the one hand those towards God, the others on his fellow men (Tirmidhi, #1955). It can be inferred that the Muslim has to give up his own interests on occasions when it came to improving the state of society as a whole (3: 93).

The case of interest falls precisely in this category, because Islam assigned to man a duty to immediately help those in need. As for the sums borrowed to meet the basic needs or for an urgent case, Islam goes further by urging to grant an additional grace period, or even to cancel altogether, the sum borrowed by the one who was not able to repay it (2: 281). The goal of the prohibition of interest (2: 276) was therefore not symbolic, but was intended to create in him noble feelings towards his neighbour. Instead of promoting inequality through interest, the Holy Book offers an alternative by encouraging the practice of charity (2: 272 & 277). The underlying idea of the universalism of the prohibition of interest was that all human beings were brothers, and therefore had to help each other financially as well as by other means.

Other Economic Measures

When we read between the lines of the Holy Book, we realize that the root of social ills was a bad attitude towards wealth and the related growth of individualism and egoism. Considering themselves as independent individuals and not as leaders of a tribe or clan, merchant leaders became selfish and careless in their traditional obligations to their members, and even to those of their own families. In addition to the poor, the orphans find prominent mention because the fathers of young dying families were numerous, and it was easy for the future guardian to appropriate his property by excluding the children of the deceased. Some verses from the Holy Book thus detail the rules for the division of an inheritance after the death of a person (4: 12-14).

Inheritance Laws

It is observed that according to this law, the woman has not only obtained a right to inherit but she receives, like her husband, the right to contract debts and to bequeath his property. To give women a position of economic independence, Islam then stipulated that any property that a woman acquired by her own effort or inherited by right belonged to her independently of her husband (Khan, 2008). Despite this measure, we still notice that men have twice the share of women. Islam assigns an extra share to the man because he has an obligation to financially support his wife and children. In the part that belongs to him, there is one of two shares that he does not possess entirely, counterbalancing the principle according to which he has the obligation to give the woman a dowry (mehr) at the time of the marriage (4: 5). Thus the inheritor, male or female, will not be able to inherit more than a third for purely personal use according to the testamentary directions.

Market & Consumer Protections

Secondly and against all odds at the time, Muhammadsa discouraged any interference in the pricing process by the state or individuals. History informs us that prices had risen in the time of the Prophet, and that many people came to him to ask him to set a limit. He said: “God is al-Musa’ir [the One who fixes the prices], al-Qabid [the One who withdraws/restricts], al-Basit [the One who increases/extends] and ar-Razzaq [the One who provides) (…)” (Ibn Majah, #2200). In other words, the Prophet enjoined to leave prices, whether high or low, “in the hands of God” (Abu Yusuf, 1921).

If merchants were free to set prices, either by increasing them (in order to increase profits on each sale) or by reducing them (in order to increase market share to the detriment of competitors), competition between them was also going to take a radical turn. Indeed, Muhammadsa combined injunctions against government intervention in pricing with a prohibition of monopolies and insider trading. “No one hoards, he would say, but the sinner” (Muslim, #1605). In markets where food supplies were as precarious as those in medieval Arabia, each famine offered the temptation to reap huge profits from desperate buyers willing to pay any price to avoid starvation. This practice (ihtikar, or more generally that of hoarding) was, as we have seen, commonplace in pre-Islamic Arabia. Sound competition also required the prohibition of other forms of exploitation of market power, for example by favouring certain competitors over others. Moreover, while insider trading is generally set in the context of contemporary financial markets, the offence has an older origin since Muhammadsa had already identified it in due course. Such was the case in Arabia, where merchants who had advanced knowledge of the arrival of a caravan would have a habit of intercepting it on the way and concluding the transaction before it reaches the market. Muhammadsa then discouraged this unfair practice known as talaqqi, and forbade the merchants to meet the caravans with the intention of buying their goods at the lowest possible prices (Bukhari, #2165, #2166 & #2167).

In order to protect the consumer, the Holy Book also highlights a number of protections against possible malpractice of the merchant. The Holy Book begins by denouncing categorically the use of unjust means and introduces the idea of mutual consent in a transaction (4: 30). Referring to merchants, chapter 83 also prohibits all kinds of misdeeds (83: 2-4). Sellers also have the responsibility to disclose any defect in the merchandise that allows the buyer to make an informed decision and not mislead him (Ibn Majah, #2247). For instance, one day, as the Prophet passed by a seller, he happened upon a pile of food. The top rice seemed dry, but when he put his hand inside, he felt that the lower layers of rice were moist. When he asked him the reason, the owner said that rain had fallen on it. He then stated that “Whoever cheats, he is not one of us” (Tirmidhi, #1315).

Market Regulators & Contractual Obligations

The first Islamic markets did then highlight the appointment of a person as market superintendent by the Prophet Muhammadsa (Sadr, 2016). We know that he appointed Sa’id ibn al-‘As as the inspector of the Meccan market and ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab to oversee Medina’s one, or Samra bint Nuhayk who presumably had jurisdiction over the female section of the market. In addition, in order to protect the parties to the transaction from possible conflict, the Holy Book states to record any fixed term written debt (2: 283). Loans and debts were then commercial standards that Islam fully supports without becoming a tool of exploitation. Indeed, the Holy Book, as we have seen, calls for sufficient time for the debtor to repay his loan in case of difficulty.

However, he has to make an effort to repay his obligation in due time because “the best amongst you, says the Prophet, are those who are best in paying off debt” (Muslim, #1601). The business community were therefore be instructed to be honest, sincere and magnanimous because “the merchant will be resurrected on the Day of Resurrection with the wicked, except the one who has fear of Allah, who behaves charitably and is truthful” (Tirmidhi, #1210).

Conclusion

It should be clear that Weber’s explanation of western capitalism being born of a Protestant Ethic is a short-sighted reading of history. Protestant Christianity was by no means unique in promoting economic activity as an act with strong moral and spiritual dimensions. Islam did the same, and to a far more explicit degree than Protestantism.

Moreover, the myriad economic injustices that western capitalism has brought bear striking resemblance to pre-Islamic Arabia. It was Muhammadsa, with the religion of Islam that catalysed a revolution in every sense of the word. Through Islam, economic principles were set out that quickly gave rise to an immensely prosperous empire. At the heart of its economic spirit was a strict sense of divine justice. Wealth was not to be accumulated for purely personal gain – indeed, this would make one egoistic and deserving of divine displeasure. Instead wealth was to be distributed towards those in need, thereby earning divine reward. Money could no longer concentrate in the hands of first-born males. Instead, it was quickly redistributed through firm inheritance laws down into all family members, penetrating widely into society within a few generations. Interest, a mechanism of redistributing wealth from the needy to the wealthy was abolished, with charitable loaning and fair investment taking its place. Price fixing, insider trading, and dishonest practices in general were also removed. In a world crying out for an alternative to capitalism, perhaps Islamic economic principles have as much relevance today as they did then.

In the spirit of his mission, Muhammadsa was not a historical anomaly. He emphasised on many occasions that his mission was not different in essence from the prophets who preceded him. Justice for all based on the cooperation of all was the best guarantee for both peace and prosperity. The true innovation of Islam was the strict application of the principles of mutual cooperation for the common good (Shaban, 1971). With a brilliant sense of direction, Muhammadsa never lost sight of this ultimate end. He enacted subtle changes that had a large cumulative effect, representing both the victory of his moderate revolution and the successful establishment of a world religion.

Fascinating read, great job by the author!

5

4.5